And I’ve been thinking about the permission to speak freely.

“O come, desire of nations, bind, in one the hearts of all mankind

Bid now our sad divisions cease and be Thyself, our king of peace”

– O Come, O Come Emmanuel

In Luke 1, after a series of otherworldly experiences, a certain priest by the name of Zacharias was finally given the freedom to speak.

At the beginning of his gospel, Luke introduces Zacharias and his wife Elizabeth who were both, “well advanced in their days” and without a child. By the end of the first chapter they have become parents and Zacharias — who had been silenced by the angel for a lack of trust — was now a man who had a word to say.

Advent is a season of waiting and Zacharias understood this waiting well. For nine months he was quiet, experiencing a mute tongue and playing charades to communicate. Ultimately, he waits through a season of pregnancy, which is, in its own right, an anticipation of an advent.

And though we can know without any doubt that the season was more physically strenuous on Elizabeth, Zacharias the priest undoubtedly felt the struggle of being silenced.

Something changes, however, when the new father writes down the name of his son, John, on a tablet for all to see. Verse 64 says that “on the instant his mouth and tongue were set free, and he spoke, blessing God.”

So what does Zacharias say when his tongue is finally liberated?

What are the first words you would say? If you were unable to speak for the length of a pregnancy, would you choose your words carefully or begin to ramble? Would you sing a song or shout out loud? Would you start with a whisper?

The first words we hear from Zacharias is a promise of freedom.

We don’t know for sure what went on in the mind of Zacharias while he couldn’t speak. Was he constantly frustrated? Did he enjoy the silence? Was he, as I heard someone say recently, “slowed down to a place of discernment”? Is it possible that the old priest came to a greater understanding of God as he pondered anew the promises of the prophets?

Whatever it was, when the Holy Spirit filled the mouth of Zacharias, his voice spoke of liberation.

It must not be a coincidence that a man who was a slave to speechlessness, speaks of freedom when the word of the Lord fills his voice.

He says in Luke 1:68,

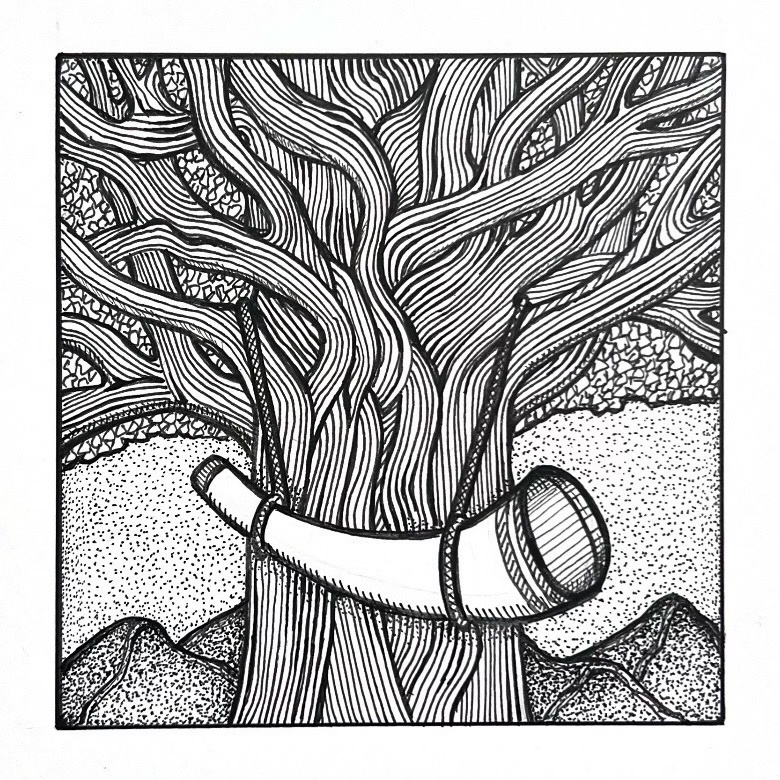

“Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, because he has visited his people and brought their liberation, and raised a horn for us in the house of David, his servant…”

Though God punished Zacharias for not trusting the angel’s message, the restoration of the priest’s mouth reveals a resolute trust in the promise of God.

Why does God visit his people?

According to the Spirit driven word on the tongue of Zacharias, God visits to bring freedom.

God visits to liberate.

Liberate from what?

The hands of their enemies, Zaharias says.

For God’s people there was a clear oppressor. An obvious opposition in Rome. And Zacharias does speak to this. But, we also can see that he is speaking to something more cosmic and universal than his personal experience. Reading today, we inevitably have to consider who we see as our enemies. And then, we must ask: Who sees us as their enemy? Who does God need to set free from us?

And then, maybe most importantly, who are God’s enemies and how does he feel about them? Should our enemies be any different than God’s?

To make matters more interesting, what does it mean that the prophetic message of Zacharias concludes with God’s desire that his people know salvation and that God is a forgiver of sins? That he guides his people’s feet into the path of peace? (Luke 1:77-79)

To me, this sounds like God is not only setting people free from their enemies, but setting them free from having enemies at all.

And what Zacharias wants to make abundantly clear is that the God he speaks for is not their enemy, but their Savior.

God visits to make his people free. Free from sin and free from death.

And free to changed.

From something as simple as liberating a mute tongue and filling it with the Holy Spirit, to liberating the cosmos, God is free to set all things free, so that he might bind them to Himself.

This is a world altering, cosmic redemption promise.

Fleming Rutledge, when writing about this verse says, “We need to know that this news is able to transfigure the ugliest shepherds, the most birth-damaged babies, the violated pregnant women dead in the ditches of the war-torn countries of this world.”1

She is right. And she is merely scratching the surface.

This Advent, we do not simply wait for a cute nativity scene to come to life. We are hoping in the visitation of God. We trust that he will bind in one the hearts of all mankind and bid our sad divisions cease. That he will free us from our own game of charades and give us the truth to speak. That he will free us from our old ways of thinking and open our eyes to His plan of salvation.

We trust that God will bring about freedom from our enemies so much so that they are not merely abolished from our presence but transfigured as our friends.

Rutledge, Fleming “Advent: The Once and Future Coming of Jesus Christ” p. 379

Leave a comment